Townhouses remain a big missing piece in Toronto’s affordability puzzle

In most of the country, townhouses are an in-between option for home buyers: bigger than the most affordable condo apartments, but smaller and more affordable than the average detached house. When researchers talk about the Greater Toronto Area’s “missing middle,” odds are they are talking about townhouses.

Given that the market still has significant affordability challenges, it may be surprising to learn sales of new townhouses in the Toronto area are now on a two year-slide, in absolute terms and as a share of all new homes. That’s despite the fact townhomes accounted for 18 per cent of all starts and 38 per cent of single-family starts in 2017, according to research from Altus Group.

“I think this year is the bottom. We’re going to see more product being released over the next few months in general,” says Patricia Arsenault, executive vice-president of research consulting services and data solutions at Altus Group.

The region’s sluggishness looks worse on a per-capita basis: There are 2.4 million people in Greater Vancouver and that market sold 3,086 new towns in 2017, while the GTA (with more than double the population at 6.4 million) offered up just 3,396 in the same year. The trend in the first half of 2018 is even more stark: just 885 new townhomes were sold in Toronto while Vancouver sold a thousand more (1,867). Other markets are growing their shares of townhome starts, too. Nationwide, they were 24 per cent of all single-family starts in 2017, and reached more than 28,000 starts in 2017, both record highs in Canada.

Altus research says townhouse buyers skew toward families: 34 per cent are under 50 years old with children, another 17 per cent are couples with no children. The largest share of buyers of new detached and semi-detached homes is also households with children (48 per cent), and the largest share of new condo apartment buyers were singles (37 per cent) followed by couples with no children (16 per cent).

“Townhomes are the way of the future,” said Howard Sokolowski, former co-owner of the Toronto Argonauts CFL team and the co-founder and chief executive of developer Metropia Inc. “The days of the single-family home in Toronto are becoming to be less and available – they are just simply too expensive. The best alternative to that is a low- rise; a townhome.” Metropia is partnering with Context Developments Inc. and Toronto Community Housing Corp. to replace 1,209 social housing units and add 4,000 new market-rate units – among them 224 townhouses – as part of the 100-acre Lawrence Heights project being built near Avenue Road.

Townhouses also form a big portion of a joint venture between Diamond Corp. and Kilmer Group Developments Inc. under development in the rapidly intensifying section of St. Clair Avenue West near Old Weston Road. There, a mid-rise building with 242 apartments will share a site with 104 townhomes (including a component of Habitat for Humanity units) being proposed for 2019.

Developer Metropia is partnering with Context Developments Inc. and the Toronto Community Housing Corporation to replace 1,209 social housing units and add 4,000 new market-rate units – among them 224 townhouses – as part of the 100-acre Lawrence Heights project.

“Affordability is the reason we’re doing it; home ownership has gotten to be very expensive,” said Jane Renwick, vice-president of marketing and sales for Diamond Kilmer Developments. “The mandate is to fill that missing-middle need. Land has become so expensive; in order to make the price of land work, you have to intensify it. There are sites that are east and west and north of the core, [which] will see a combination of mid-rise and townhome.”

According to a new report from Evergreen Canada, the “middle” housing option has been missing in Toronto because planning has, intentionally or not, favoured tall- building development. “From 2013 to 2017, more than 64,000 new residential units were constructed in the city of Toronto in development projects for which the tallest building was more than 12 storeys,” the report said.

Evergreen argues that because the city’s Official Plan has directed new development to areas that only account for about 25 per cent of the city’s landmass – “designated as Avenues, Centres, Employment Areas, and the Downtown and Central Waterfront” – the market has pumped up land prices in those areas to a level where eight- to 12-storey mid-rise buildings, let alone low-rise townhouses, face enormous cost barriers to construction. “The result has been growing polarization between tall, high-density

development (characterized by smaller units) and dispersed, low-density housing,” it said.

Rather than looking at adding more low-rise density to more neighbourhoods, mid- and high-rise developers have faced pressure from planning staff and politicians to build more family-sized units, even though the economics tend not to work for buyer or builder. Under plans such as TOcore, unveiled earlier this year, any building with more than 80 units in the city’s core would be mandated to make 40 per cent of its units two- and three-bedroom apartments.

“People are promoting bigger [apartments] for families, the reality is families can’t afford them … they are not buying the larger condos, which are the high end of the market in Toronto,” Ms. Arsenault said.

The Junction House condo project tried with middling success to crack the affordable code on family condos with a mid-rise development at Dundas and Dupont streets.

Brandon Donnelly, vice-president of development at Slate Asset Management, tried with middling success to crack the affordable code on family condos with a mid-rise development at Dundas and Dupont, designed by architects Superkül, called Junction House.

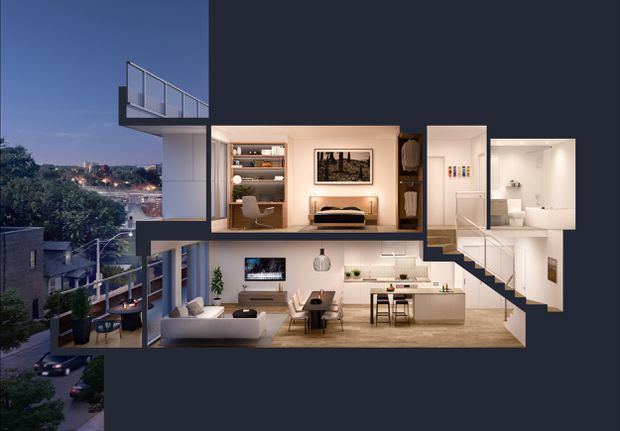

“This project started with that thesis in mind: ’Can we create a great substitute to low- rising housing … for people who don’t want to buy a house for $1.3-million and gut and fix it up?’ That was the original thesis, which is why we called it Junction ‘House,’” Mr. Donnelly said.

However, while the project was planned for 12 storeys – and would have included 65 large condo units – through the planning process, the building was chopped down to nine storeys with steeper setbacks on the higher levels, so half of those family units were axed from the program. “Unfortunately, height trumps a lot of other concerns,” Mr. Donnelly said. What remains is 144 total units, of which 24 are two-storey apartments in the middle of the stack and seven are similar sized towns at grade. At any rate, while it is an increase in supply, those units were never going to be much cheaper than detached homes in the surrounding area.

“We spent a lot of time on how we could design those in a way that was reasonable and competitive with other low-rise two-storey suites. We’re just over 1,000 square feet on a two-bed, two-bath unit,” he said. The price? $1.1-million and up, comparable to other resale single-family homes in the area.

Not that a lot of new GTA townhouses are a significant bargain by comparison.

Metropia’s towns will range in size from 2,500 square feet to 1,400 square feet, ranging from more than $1-million to about $700,000 for the smallest units. “The average family with two kids can afford $700,000,” Mr. Sokolowski said. “At today’s interest rates and qualifications levels, they need a combined income of $200,000 to afford that.”

The reality is likely only a small chunk of Toronto families live in that income bracket. According to Statistics Canada, in 2015 the median household income for families in Toronto age 25 to 34 was $69,710, although it shoots up to $105,710 for those aged 45- 54 years. Also, while Toronto has the country’s highest proportion of residents earning $100,000 a year, it’s still only 10.5 per cent of the population.

The Junction House condo project was planned to be 12 storeys but was chopped down to nine, meaning half of the planned family units were axed from the program.

Statistics on the GTA’s average townhouse size are also out of whack with the rest of the country: Driven by a large collection of so-called “executive towns” in exclusive

neighbourhoods, GTA townhouses average 2,100 square feet. That’s dramatically bigger than the average in Canada’s two fastest-growing townhouse markets – Edmonton and Calgary – which average 1,400 and 1,300 square feet, respectively. The GTA price per square foot is also high at $400, second behind Vancouver’s $575. That suggests the average new GTA townhouse is $840,000, compared with $315,000 in Edmonton.

The other issue with townhouse projects is that it takes a while to sell them out. Even with a relatively short build cycle (from presales to move-in can be under two years in some situations, unlike the three or four or more years typical of high-rise), families can’t always wait that long for their housing to arrive.

Ms. Arsenault said there are more than 2,600 units of unsold townhouse inventory in the GTA as of September, a sign that buyers are still hesitant to pull the trigger. The vast majority of those unsold units are located in communities that have seen significant detached-home price drops since 2017 – York, Peel and Durham (980, 656 and 633 units) – while Halton and Toronto have the smallest available inventory (226 and 166 units, respectively).

Source: Globe and Mail